It’s a 2.5 hour drive from Turmi to the Karo village of Korcho through an idyllic slice of untouched rural Africa. There are no power lines, communication towers, or any other suggestion of the modern world. There is nothing taller in fact than an acacia tree or a brick-red termite mound. Much like yesterday we pass many tribes people (predominantly Hamer, this being Hamer territory) during our journey. Fekede, our driver-guide, promises we will meet the Hamer tomorrow, but today is devoted to the Karo. These are perhaps the most endangered of all the tribes people in the Lower Omo Valley, numbering little more than 1000. Their territory is on the east bank of the Omo river, squashed between the Hamer to the south and the Banna to the north. Originally pastoralists, they now survive by practising agriculture.

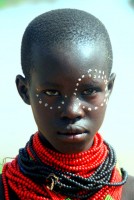

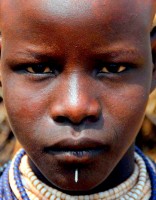

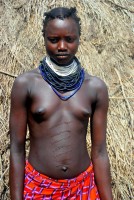

As usual Fekade approaches the village chief asking for permission to visit the village and once a ‘present’ exchanges hands Christi and I are free to wander around. The village of Korcho lies on a bluff above the Omo river, which Christi and I are seeing for the first time. It may not have the fame of the Amazon or the Nile, but without it the complex melding pot of ethnicities would not exist in this area. The Karo are friendly and much like the Mursi eager to be photographed. Okay, that might not be entirely true, but they know that they only way they can earn money is by posing before the camera. And sometimes they go to ridiculous lengths to attract my attention: the girls all pose topless (which does get my attention), while others paint their bodies (the Karo are famous for their body painting using white chalk, which they do normally in preparation for dances, feasts, and celebrations). Many of the young women have a pierced lower lip with an inch-long nail protruding. And yet others have short hair dyed red, the result of mixing animal fat and the pigment ochre.

The experience of being in the village is something of a photographic frenzy. Perhaps the Karo assume that all tourists want to take photographs, which is probably true but it’s then difficult to learn much about the culture of these people when I’m literally forced to take photos. As soon as one person has collected their fee from Christi the next person – man, woman, child takes their place, demanding to be photographed so they too can collect money from Christi. In the end, and I can’t believe I’m saying this, I have to ask Fekade to intervene and the locals to give me some breathing space. An envoy of the chief takes us on a brief tour of the village and we are accompanied at a discreet distance by an entourage of locals who are waiting for the moment when I start taking photos again. We do learn that Karo, Hamer, and Banna are all related to varying degrees and intermarriage between tribes is possible. This is not the case with the Bumi tribe who live further to the south and who are the sworn enemy of the Karo. A rite of passage shared by the Karo and the Hamer is the Jumping of the Bulls ceremony. This is performed by teenage boys as they transition into manhood. In fact many Karo youths are currently attending this ceremony at the village of Kangatan (the largest of the Karo villages) further to the west. It is clear that Christi and I will be unable to leave the village until I take a few more photos and we brace ourselves for the onslaught. We are tired, financially poorer, but ultimately very privileged to have shared time with the Karo when we finally say goodbye.

Blog post by Roderick Phillips, author of Weary Heart – a gut-wrenching tale of love and test tubes.

Speak Your Mind